Cupid de Locke Lyrics: Cupid hath pulled back his sweetheart's bow / To cast divine arrows into her soul / To grab her attention swift and quick / Or morrow the marrow of her bones be thick / With. In most cases, there was no evidence of organic disease. Corrective nutritional guidance dispelled these unpleasant symptoms for many spouses and in the process often bolstered their crumbling marriages.” The doctor tells of the case of Mrs. R.L, a 34-year-old secretary. Mac OS 8 (2,202 words) exact match in snippet view article find links to article system-wide antialiasing for type was also introduced. The HTML format for online help, first adopted by the Finder's Info Center in Mac OS 8, was now used.

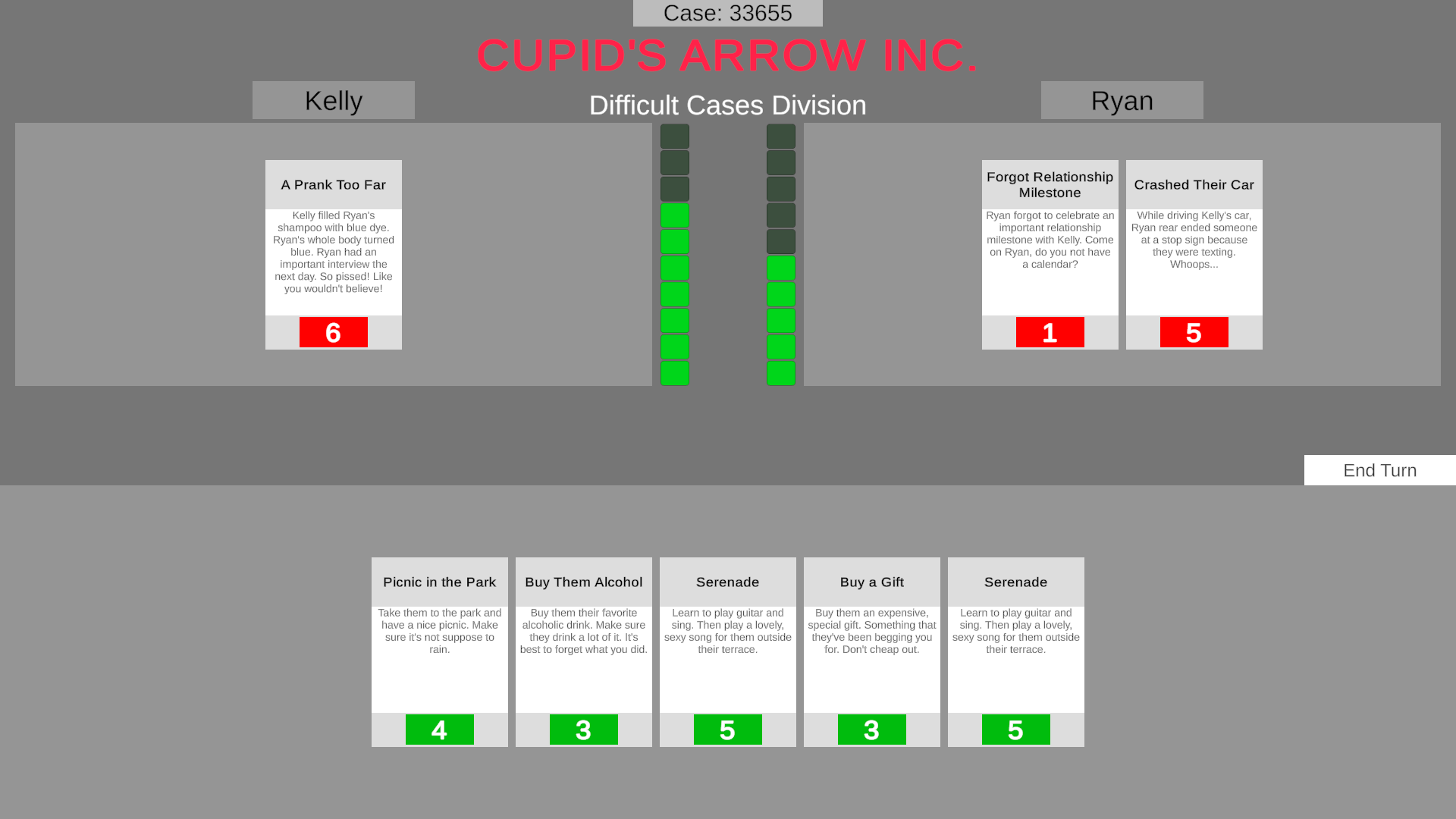

- Cupid's Arrow Inc. Difficult Cases Division (solitudedude) Mac Os Update

- Cupid's Arrow Inc. Difficult Cases Division (solitudedude) Mac Os Download

- Cupid's Arrow Inc. Difficult Cases Division (solitudedude) Mac Osu

- Cupid's Arrow Inc. Difficult Cases Division (solitudedude) Mac Os X

[Civ. No. 11431. First Appellate District, Division Two. August 22, 1940.]

[Civ. No. 11431. First Appellate District, Division Two. August 22, 1940.]IAN L. MacDONALD, Petitioner, v. THE SUPERIOR COURT OF SAN MATEO COUNTY, Respondent.

COUNSEL

Edmund G. Brown and Harold C. Brown for Petitioner.

Frank V. Kington for Respondent.

OPINION

Sturtevant, J.

This is an application for a writ of mandate. Facts material to the application are as follows: On July 19, 1939, the petitioner commenced an action to obtain a divorce from his wife, Bessie E. MacDonald. The action was commenced in San Francisco, but on application of the defendant an order was entered transferring the case to the county of San Mateo. On September 25, 1939, the Superior Court of the State of California, in and for the County of San Mateo, made an order directing the petitioner to pay to the defendant $50 per month as maintenance pendente lite, the further sum of $15 on account of costs, and $50 on account [40 Cal. App. 2d 518] of attorney's fees for defendant. At all times herein mentioned the defendant had and has an income of $250 per month. On January 22, 1940, the petitioner served and filed a notice of motion for an order modifying the previous order for maintenance, costs and counsel fees, and in support thereof he served and filed an affidavit. On March 4, 1940, said motion came on for hearing. At that time petitioner was present and represented by his counsel. The defendant was present and represented by her counsel. The trial court refused to countenance, entertain or hear the petitioner's motion, stating that the petitioner had not complied with the order dated September 25, 1939. The record does not disclose that at any time or at all, any proceedings have been had charging the petitioner as being in contempt or that any order or judgment to that effect has been entered.

The record does not disclose that the petitioner has paid any part or portion of the sums specified in the order dated September 25, 1939. The affidavit above mentioned tendered in support of petitioner's motion set forth that the petitioner has not been employed since September 13, 1939, although he has, on numerous occasions, attempted to obtain work and employment; that the defendant is steadily employed on a salary of $200 a month and has additional income in the sum of $50 per month; that the petitioner is in a highly nervous and excited condition and his doctor has recommended rest; that petitioner is willing to comply, and will, as soon as he is able, comply with the order made September 25, 1939.

The nature of the modification asked by the petitioner is stated by him as follows: 'The said order now reads that said plaintiff shall pay to said defendant the sum of $50 per month, beginning on said 25th day of September, 1939, and the further sum of $50 on account of attorney's fees; and your said plaintiff desires that said order be modified by eliminating therefrom any further payments in the sum of $50 per month until the trial of said action.' In other words, the request of the petitioner is in effect to limit his obligations before the trial is had to the payment of $50 as attorney's fees, and $200 as maintenance of the defendant.

[1] From the foregoing facts it is obvious that the petitioner may be said to be in default, but it is equally clear he may not be said to be in contempt. No party to an action can, with right or reason, ask the aid and assistance of a court in [40 Cal. App. 2d 519] hearing his demands while he stands in an attitude of contempt to its legal orders and processes. (Weeks v. Superior Court, 187 Cal. 620, 622 [203 P. 93]; Schubert v. Superior Court, 109 Cal. App. 633 [293 P. 814]; Funfar v. Superior Court, 107 Cal. App. 488 [290 P. 626].) However, it is settled law that one, who is not in contempt but through an abundance of caution makes a timely application to be relieved from an order which, if allowed to stand, may in the future become the basis of contempt proceedings, is entitled to have such application heard and determined. (Manriquez v. Superior Court, 199 Cal. 749 [251 P. 1118]; Isakson v. Superior Court, 130 Cal. App. 180 [19 PaCal.2d 840]; Archer v. Superior Court, 81 Cal. App. 742 [254 P. 939].)

[2] The trial court confused the foregoing rules. The confusion resulted in the court erroneously divesting itself of jurisdiction. Such facts clearly support the application now before us. (Golden Gate Tile Co. v. Superior Court, 159 Cal. 474 [114 P. 978].)

The defendant's attorney has filed an answer 'for the respondents.' In it they admit all of the foregoing propositions of law and fact. But they set forth facts and figures showing or tending to show that the defendant needs the benefit of all of the moneys allowed to her by the terms of the order dated September 25, 1939. Be that as it may, such issues are the very ones the plaintiff sought to have heard and determined by the motion which he sought to have heard and determined and which the trial court refused to hear.

Let a peremptory writ of mandate issue as prayed.

Nourse, P. J., concurred.

We’ve heard the clichés: “It was love at first sight,” “It’s inner beauty that truly matters,” and “Opposites attract.”

But what’s really at work in selecting a romantic or sexual partner?

University of Notre Dame Sociologist Elizabeth McClintock studies the impacts of physical attractiveness and age on mate selection and the effects of gender and income on relationships. Her research offers new insights into why and when Cupid’s arrow strikes.

In one of her studies, “Handsome Wants as Handsome Does,” published in Biodemography and Social Biology, McClintock examines the effects of physical attractiveness on young adults’ sexual and romantic outcomes (number of partners, relationship status, timing of sexual intercourse), revealing the gender differences in preferences.

“Couple formation is often conceptualized as a competitive, two-sided matching process in which individuals implicitly trade their assets for those of a mate, trying to find the most desirable partner and most rewarding relationship that they can get given their own assets,” McClintock says. “This market metaphor has primarily been applied to marriage markets and focused on the exchange of income or status for other desired resources such as physical attractiveness, but it is easily extended to explain partner selection in the young adult premarital dating market as well.”

McClintock’s study shows that just as good looks may be exchanged for status and financial resources, attractiveness may also be traded for control over the degree of commitment and progression of sexual activity.

Elizabeth McClintock

Among her findings:

Cupid's Arrow Inc. Difficult Cases Division (solitudedude) Mac Os Update

- Very physically attractive women are more likely to form exclusive relationships than to form purely sexual relationships; they are also less likely to have sexual intercourse within the first week of meeting a partner. Presumably, this difference arises because more physically attractive women use their greater power in the partner market to control outcomes within their relationships.

- For women, the number of sexual partners decreases with increasing physical attractiveness, whereas for men, the number of sexual partners increases with increasing physical attractiveness.

- For women, the number of reported sexual partners is tied to weight: Thinner women report fewer partners. Thinness is a dimension of attractiveness for women, so is consistent with the finding that more attractive women report fewer sexual partners.

Another of McClintock’s recent studies (not yet published), titled “Desirability, Matching, and the Illusion of Exchange in Partner Selection,” tests and rejects the “trophy wife” stereotype that women trade beauty for men’s status.

“Obviously, this happens sometimes,” she says, pointing to Donald Trump and Melania Knauss-Trump as an example.

Cupid's Arrow Inc. Difficult Cases Division (solitudedude) Mac Os Download

“But prior research has suggested that it often occurs in everyday partner selection among ‘normal’ people … noting that the woman’s beauty and the man’s status (education, income) are positively correlated, that is, they tend to increase and decrease together.”

According to McClintock, prior research in this area has ignored two important factors:

Cupid's Arrow Inc. Difficult Cases Division (solitudedude) Mac Osu

“First, people with higher status are, on average, rated more physically attractive — perhaps because they are less likely to be overweight and more likely to afford braces and nice clothes and trips to the dermatologist, etc.,” she says.

“Secondly, the strongest force by far in partner selection is similarity — in education, race, religion and physical attractiveness.”

Cupid's Arrow Inc. Difficult Cases Division (solitudedude) Mac Os X

After taking these two factors into account, McClintock’s research shows that there is not, in fact, a general tendency for women to trade beauty for money.

“Indeed, I find little evidence of exchange, but I find very strong evidence of matching,” she says. “With some exceptions, the vast majority of couples select partners who are similar to themselves in both status and in attractiveness.”

Contact: Elizabeth McClintock, 574-631-5218, emcclint@nd.edu